What "Linux Operating System" do you use? (INCOMPLETE)

This post is to help you learn the basics of (mostly) everything so you can see the full picture. If you have no idea what you're doing or if you're new to Linux, this post is for you. There are a billion different misconceptions, misunderstandings, and incorrect interpretations of concepts related to Linux, and in this post, we'll debunk them. I'm disappointed by the fact that nobody has written something like this before. There are plenty of YouTubers and content creators who post multiple videos a week, but none of them talk about this stuff. Absolutely pathetic! This guide will assume you're a Windows user. If you're a macOS user, you shouldn't have made it to my blog.

Note that I'll only be touching the surface of every key highlight with very brief descriptions to keep things simple. The goal here is to help you see the full picture, not to learn/master everything.

At the very low level, you have your hardware.

Linux Kernel

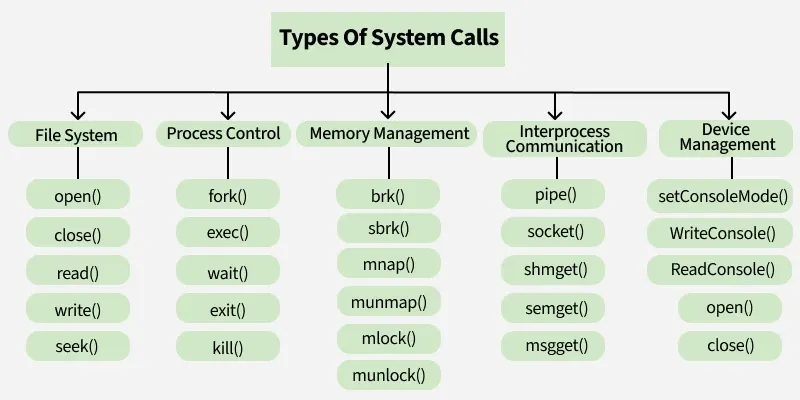

An operating system is not just one software. They consist of multiple major components. At the core is the kernel. The kernel has direct access to hardware and memory. Other "user space" applications are not allowed to communicate with the kernel directly. Instead, they have to call something called system calls (commonly referred to as "syscalls"). Every time a program needs to read a file, allocate memory, or send network data, it's the kernel that actually does it on behalf of that program.

Your "Windows 11 Operating System" uses Microsoft's proprietary Windows NT kernel, which you cannot legally or technically modify. In "Linux" systems, the kernel is Linux, created by Linus Torvalds in 1991. This is an open source project (licensed under GPLv2), meaning you can inspect its code, patch it, recompile it, and even redistribute own version.

On top of that, the kernel is what handles process scheduling, memory management, file systems, networking and all the other low level operating system related functions.

Kernel Modules

This is a piece of code that can be dynamically loaded into or unloaded from the linux kernel at runtime without having to reboot the system. Kernel modules allow us to extend the functionality of the kernel in a very modular way. These modules are usually found inside the /lib/modules/$(uname -r)/ directory.

Below is an awesome, more technical explanation of what these are.

"The quick and short way to explain kernel modules is that they are a binary file, kinda like a shared library, which the kernel will map into its address space. These modules can expand kernel functionality. This functionality can be different between different kinds of kernel modules. What people are mostly talking about in regards to kernel modules are drivers. However, kernel modules can be anything from that to filesystem interfaces and security mechanisms." - Reddit

mod is how you usually refer to kernel modules in short. The lsmod command will list all the loaded modules, insmod will insert a module and modprobe will insert a module but it will also resolve the dependencies, rmmod will remove a module and modinfo will show module information. These are some commands that you will eventually run in to (mostly when having to deal with drivers in a general purpose context)

You can learn more about kernel modules in this Arch Wiki page.

Kernel Headers

These are C header files (.h) that's usually placed inside /usr/src/. They define an "interface" which specifies how functions in the source files (.c) of the kernel are defined. They are used so that a compiler can check if the usage of a function is correct as the function signature (return value and parameters) is present in the header file. Yes, again, these are just C header files - all they do is define declerations of functions as shown below:

int foo(double param);

They are used to

- define interfaces between components of the kernel, and

- define interfaces between the kernel and user space

Or in simpler terms, they basically tell the c compiler how to recompile everything in a way that it will be able to communicate properly with the new kernel version. You need them for installing almost anything compiled against that kernel. In Arch Linux, these header files are managed by a seperate package named linux-headers. In Debian, this package takes the format: linux-headers-$(uname -r).

You can learn more here or here.

Device Drivers

Just above the kernel sits device drivers. These are small programs that tell the kernel how to talk to your specific hardware, like graphic cards, wifi adapaters and what not. In Linux, many drivers are built directly into the kernel or distributed as loadable kernel modules (LKMs) that can be dynamically added or removed (sometimes at runtime, without requiring restarts). The drivers that are distributed seperately and that has to be loaded by the user according to their requirement are sometimes also referred to as "out of tree drivers".

Graphics Drivers

One commonly talked about topic related to drivers in Linux is the graphics drivers for NVIDIA and AMD GPUs. If your GPU is AMD, the built-in drivers should have you covered.

Back in the day, AMD's Linux driver support wasn't always great. Years ago, AMD provided a closed-source driver called fglrx, which was often buggy and hard to maintain. Eventually, AMD realized that open collaboration with the Linux community was the best way to go. Therefore, they open-sourced large parts of their driver stack, and today the AMDGPU driver (maintained directly in the Linux kernel) and Mesa's open-source 3D stack deliver fantastic performance. As a result of this, if you own an AMD GPU, most modern distributions should support it out of the box without you having to install anything. It will just work!

If you have an NVIDIA GPU, your life gets a little complicated. You have two options:

- The proprietary NVIDIA driver provided by NVIDIA themselves.

- The Nouveau open-source driver, maintained by the Linux community.

If you just want to get on with life, you should consider using the proprietary driver over the open-source one. If you have ethical or freedom-related reasons, use the open-source driver. But if you're new to Linux and you want to use your hardware to its fullest potential, use the proprietary driver (like I do). While the latest versions of Nouveau and the proprietary driver might seem similar, the proprietary driver still tends to perform better and gives you access to all the advanced features of your GPU like CUDA, NVENC and full 3D acceleration.

NVIDIA has refused to fully open-source their driver stack multiple times, and this has long been a pain in the pass in the Linux community. The situation between NVIDIA and Linux has been so frustrating that Linus Torvalds himself once famously said, "Fuck you, NVIDIA". This video can be found here.

While I was writing this, Nvidia released their 590.XX which drops comapitbility for GPU's based on architechtures older than Pascal and Maxwell (both ~10 year old chipsets). This breaks a lot of compatibility. I've written an article covering everything that happened and it can be found here on my blog or on medium.

Wi-Fi Adapters

Another commonly talked about area is WiFi adapters. Most of them should work out of the box with the generic drivers included in the Linux kernel. Modern distros ship with a wide range of wireless drivers pre installed, so in many cases your Wi-Fi will just work out of the box.

If it doesn't, your next step is to check whether there's a package available for your adapter (we'll talk more about packages later). Many vendors and community maintainers publish driver packages that can be installed directly using your distro's package manager. They are usually named like broadcom-wl or rtl8821ce-dkms and so on.

If you can't find an official package, try searching online (especially on GitHub) to see if someone from the community has written or ported a driver for your chipset. If you find one, you can usually compile it from source and pray for it to work.

If you've tried all that and still can't get it to work, just give up at this point. Buy a new WiFi adapter that supports linux out the box to use

DKMS

If you refer to the package name above (rtl8821ce-dkms), you can see the -dkms suffix. This means that this package is a DKMS package. DKMS stands for Dynamic Kernel Module Support. It basically means that it will help the kernel module (in this case, it's the wifi driver) to stay compatible after changes to your linux kernel like updates. Normally, kernel module (drivers) are compiled specifically for the version of the kernel you are running. If you update the kernel, it might break support for these kernel modules as they were built for the old kernel. Therefore, we have to rebuild the driver module using the new kernel headers. The packages that has the -dkms suffix by convention will take care of that building on its own - so that you don't have to worry about your drivers breaking in you update your kernel. A common example of this is the nvidia-dkms package. This will just re-build the driver automatically after you update your kernel to ensure everything is working smoothly.

Init System

In the boot process of a linux system, once the kernel loads, a special userspace program called the "init system" starts. The kernel launches this with a PID (Process ID) of a 1. This acts like the root of all other processes. An init system is responsible for orchestrating the boot process. It starts all the other system services, handles shutdown and reboot sequences, and managed all the system services.

Historical Init Systems

SysV Init

In linux systems, there are multiple init systems. At the very beginning, everything used the "SysV Init" system - short of System V Init. This was built to function like Unix System V. This uses 0-6 different run levels to define boot states and to make things simple, it is script based. All the init scripts are stored inside /etc/init.d/. Here, all the services launch sequencially (via those scripts) - therefore, resulting in a slower startup times. This init system is simple and easy to use but it lacks a lot of modern features like parallel startup of processes and the ability to monitor services.

Upstart

Around 2006, Canonical released Upstart - a modern alternative to SysV. This performed faster comparatively and was event based. This gave the ability to perform certain things when an event was triggered - such as "when a device appears".

Systemd

In late 2014, systemd was released. This is not just a basic init system, it is a complete system manager with modern highly sophisticated features. It introduced features like parallel startup of processes, service supervision (auto restart and service dependency ordering/management), a unified centralized logging system, a consistent configuration file format, timers and socket activation. Canonical discontinued upstart and adopted systemd for their linux distribution named Ubuntu. Most modern linux distributions use systemd as their init system.

Systemd works with service files, called units (basically configuration files). They define how a component behaves. By convention, each unit file is given a suffix to suggest the component type. Let's take a look at some of those.

.service: These are used to contain information about individual services. They are also called daemons..timer: These are used to perform shceduled jobs..mount: These are used for file system mounts..target: This is basically a group of services to start. An example isgraphics.target, which starts all the graphics related services.

A simple .service unit file can be found below. As you can see below, using things like After=, you can handle dependencies easily. Here, the After=network.target will ensure that this service will start only after network.target component has been started. A list of all these directives can be found here in the official documentation.

[Unit]

Description=MyApp Service

After=network.target

[Service]

ExecStart=/apps/myapp/executable

WorkingDirectory=/apps/myapp

Restart=always

User=serviceuser

Group=servicegroup

[Install]

WantedBy=multi-user.target

To communicate with systemd, you should use the systemctl command line utility. This blog post covers the basic usage of services with systemd along with the basic usage of the systemctl command.

Covering everything about systemd is not the goal of this article. This is already too much. You can learn more about Systemd here or here.

OpenRC

As you read above, systemd is a heavy and very feature rich. OpenRC was built as an alternative init system to systemd that is also dependency based. This is mainly used in Gentoo, Alpine and Artix Linux. It's simple, fast and unix like. This supports modern features like service dependency, parallel startup, SysV styled init scripts and many more.

However, unlike systemd, openrc does not bring it's own ecosystem with it. This increases compatibility with existing tools but it might come at the cost of inconvenience.

The Controversies

In saying that, since systemd is widely adopted, you will almost never run into compatibility issues. However, since systemd provides a more centralized interface and it tries to manage logging, network, timers, etc... - it breaks the unix philosophy of "do one thing and do it well". Some people call it bloatware and prefer the simple nature of openrc. The haters have gone as far as hosting websites like these: ihatesystemd.com.

In my opinion, the shouting voices don't represent the majority here. Systemd saves a lot of time and work for developers, packages and administrators due to its' convenience. So, it's not surprising that it has been very widely adopted.

This video below titled "The Tragedy of systemd" should give you a very good understanding about the current situation of this controvery and systemd hate.

Userspace Libraries

The kernels, drivers and the init system might be running now but that's not enough for applications to be run. User applications need a stable and a consistent way to communicate with the kernel. This is where the userpace libraries and APIs come in.

Linux based operating systems scritcly seperate the kernel space and the user space. The kernel space is the kernel, drivers, etc... and has full access to hardware and memory. Userspace in the other hand are applications, shells, services, desktop environments, etc... running with restricted privileges. Again, these userspace applications are not allowed to call kernel code directly. Instead, they interact with the kernel through "system calls".

"In computing, a system call (syscall) is the programmatic way in which a computer program requests a service from the operating system[a] on which it is executed. This may include hardware-related services (for example, accessing a hard disk drive or accessing the device's camera), creation and execution of new processes, and communication with integral kernel services such as process scheduling. System calls provide an essential interface between a process and the operating system" - Wikipedia

As mentioned above, they do everything. The image (src) below shows some of the common high level functionalities that the kernel allows you to call/access via syscalls.

And on top of these low level syscalls, higher level libraries have been built, forming a layered ecosystem.

GNU is Not Unix

It's history time again! In 1960s, UNIX was developed in Bell Labs by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie. This was one of the very first operating systems to be multi-user, mutli-tasking and portable. Most of it's codebase was written in C - a relatively high level programming language compared to what they used before that. This later evolved into multiple products like HP-UX (by Hewlett Packard), Solaris (by Oracle) and MacOS (via the BSD and POSIX heritage). UNIX introduced it's own philosophy, which also made it stand out back in the day. You can find the basics of the UNIX Philosophy here.

By the early 1980s, UNIX had become commercial and proprietary. Richard Stallman believed that this nature of software restricted the user freedom and collaboration and he launched the GNU Project back in 1983. GNU is pronounced as "GNOO" and is a recursive abbreviation for "GNU is Not Unix". His goal here was to create a completely free and open source, unix compatible operating system. Eventhough they reimplemented these tools and interfaces from scratch, to ensure compatibility, they stuck with the same unix philosphy and behaviour, so that the existing software could be ported/migrated easily. They developed compilers (gcc), shells (bash), libraries (glibc) and more importantly, the GNU Core Utilities (or GNU Coreutils for short).

Several ideas introduced by Unix are still being followed today, like:

- Everything is a file

- Heirarchial filesystem which starts at

/ - Write programs that do one thing and do it well

- Write programs to work together

- Using text as a universal interface

Due to this nature, many simple tools that does one task can be chained together to perform complex actions, like:

ps aux | grep nginx | awk '{print $2}' | xargs kill

However, GNU did not initially have a working kernel. Back in 1991, Linus Torvalds got inspired to create a kernel from scratch, without re-using any of the UNIX source code and released it under the GPL license. This was in perfect timing for the GNU Project as Linux provided the missing kernel that GNU needed.

In simpler terms, GNU had a userspace but no kernel and Linux had a kernel but no complete userspace. When they were put together, they form a fully functional, free and open source operating system. What people refer to as Linux is actually a shorthand for the whole system which consists of GNU+Linux.

GNU is short for "GNU is Not Unix" right? But it is very identical, isn't it? Yes! GNU behaves like Unix, it's compatible with Unix, but in terms of code, licensing and ownership, it's different. The nature of the licensing and ownership is "Free as in Freedom" and not "Free and in Beer". The youtube video of the Ted talk given by Richard Stallman covers some of his basic idealogies regarding software "freedom".

When someone says "Linux, now you know that they actually refer to "GNU+Linux". Due to the technical inaccuracy when referring to "GNU+Linux" as just "Linux", it let to a huge copypasta:

"I'd just like to interject for a moment. What you're refering to as Linux, is in fact, GNU/Linux, or as I've recently taken to calling it, GNU plus Linux. Linux is not an operating system unto itself, but rather another free component of a fully functioning GNU system made useful by the GNU corelibs, shell utilities and vital system components comprising a full OS as defined by POSIX. ..." - Copypasta

Busybox

Now would be a good time to learn some basics about the linux file system's structure if you haven't already. Also, look into what symbolic links are to avoid potential confusion.

GNU+Linux is what runs on desktops, servers, etc... But for embedded systems with minimal resources, GNU might be too heavy. Busybox is a single lightweight executable. It provides many common unix utilities in one single binary. Instead of having seperate binaries for ls, cp, mv, mount, ps, etc..., busybox implements minimal versions of these tools and exposes them through symlinks.

/bin/ls --> busybox

/bin/cp --> busybox

/bin/mv --> busybox

This basically means that everything is mapped to the same binary that handles all of it. The behaviour will change according to the name it is invoked as accordingly. Therefore, this technically can replace the GNU Coreutils entirely. Also, keep in mind that glibc is often replaced with musl - these are standard libraries for C. The bash shell will be replaced with ash. Most of the complex and on essential flags found in commands / features will not exist. Due to the resulting small binary size, minimal feature set and it's optimized and lightweight nature, busybox is used a lot instead of GNU in many embedded systems.

Busybox can be seen in many IoT devices, routers, set top boxes and many other network appliances which has limited storage, ram and CPU power.

Package Managers

Now, your computer has a kernel, userspace utilities (either via GNU or BusyBox), an init system and libraries required for programs to run. The problem that remains is how applications/packages can be installed, updated and removed. This is done using package managers. A package management is responsible for the distribution of packages and lifecyle management. When you attempt to install a package, it will resolve the dependencies automatically and place the files in the correct intended locations, which also allows them to be updated safely and easily.

Listed below are some common package managers based on the distribution:

- Arch Linux:

pacman - Debian:

apt - Fedora:

rpm - Alpine:

apk

To further understand how packages work, we will go through the app installation process with apt on Debian and let's also take a look at the "Arch User Repository".

Installation of Packages

The apt install <packages> command in Debian is identical to pacman -S <packages> in Arch Linux. When installing a package, the majority of package managers follow a very identical list of steps. To simplify things, I will stick with apt for the rest of this explanation.

The apt install command required root privileges to ensure access to certain system directories such as /usr, /etc, /var, etc..., modify the "package database" and install binaries, libraries and configuation files. To grant this temporirily, you usually run it using the sudo command. This will run the command with root privieleges.

Firstly, apt checks the "local package index". This is usually found inside the /var/lib/apt/lists directory. To ensure the "local package index" is upto date, run the apt update command. If it's out of date, apt will warn you. This index contains information like: package names, versions, dependencies, checksums, repository origin and many more.

Next, apt will lookup the package in all the configured repositories which are to be found inside /etc/apt/sources.list or at /etc/apt/sources.list.d/*.list. A repository is a trusted source of packages that apt will connect and fetch packages from. This is what a single line in sources.list looks like:

deb http://deb.debian.org/debian bookworm main contrib non-free non-free-firmware

Here,

debtells that this repository contains binary packages. If this value is replaced withdeb-src, it means that this package might have to be built from source. But in this example scenario, we will focus on havingdeb.http://deb.debian.org/debianis the URL of the official debian's package serverbookwarmis is the release of debian installed on the current systemmain contrib non-free non-free-firmwareare the list of repository components that I'll be accessing from here.

Note that apt will only look for packages in the sources/repositories mentioned here. If the package cannot be found here, apt would error out saying that such a package was found. These file(s) simply contain a trusted source of packages that apt will connect and fetch for packages from. Once apt has selected the best candidate version, it will verify the architecture compatibility (amd64, arm64, etc...).

Next, apt will resolve dependencies for the target package recursively and build a dependency graph. apt will also ensure that no compatibility issues arise with other packages when dealing with the dependency packages.If any dependency conflicts exist, apt will not proceed to install anything and warn the user accordingly.

If no dependency conflicts are found, apt will then show a detailed list of all the packages that will be installed. Next, it will ask for user confirmation to proceed with the installation.

Before downloading any packages, apt will ensure that the repository is trusted by verifying the GPG signatures. Each repository has a signing key. These are stored inside /etc/apt/trusted.gpg, /etc/apt/trusted.gpg.d/, /usr/share/keyrings/. apt will verify the repository metadata is signed and will also verify the .deb packages match the signed checksums. Installation will stop is a key is missing or if the GPG signature verification fails. All of this ensures that MiTM attacks and package tampering is impossible.

Then, apt will download all the .deb files to the /var/cache/apt/archives/ directory. Each .deb package contains some metadata (in the control file), the files to install and pre/post install scripts. These will later be handled by dpkg later. For now, apt will ensure the file size and file hashes to verify integrity.

Next, dpkg is invoked by apt to install each .deb package in the order of the dependency graph. The installation happens in this order:

- For each package, the

preinst(pre installation) script will run. This is used for sanity checks, to prepare directories and if the package is being upgraded, to ensure the migration of old configuration files. - The installation files will be extracted to

/usr/bin,/usr/lib,/usr/share,/etc, and other required directories. Now, the package has been installed. - After unpacking, the

postinst(post installation) script will run. This may register MIME types, update icon caches, register apps with the system, etc..ldconfigis run to update/etc/ld.so.cacheand other files that will create symbolic links and cache for shared libraries. When integrating with the system, it may install systemd unit files, update udev rules, add entries to the desktop environment being used, and do similiar stuff. - Once the package installation and configuration is complete,

dpkgwill add it to it's package database to keep track of it easily. This will allow for easy upgrades, depedency tracking and clean removal in the future.

Optionally, at the very end, you can run a command like sudo apt clean to remove the temporary files used while the installation was going on.

This concept applies in an almost exact way to pacman too. Of course there will be differences in certain names, directories and what not but the concept is fundemantally the same. A local package database is synchronized with remote repositories, depedencies are resolved, packages are downloaded from configured sources, their signatures are verified and software is installed. This concept remains the same across most modern linux package managers.

Arch User Repository

I know this post was supposed to be a generic for all linux distributions but because of my personal bias, I will mentioned this too. However, do note that this is relevant for Arch Linux only. (I use Arch btw).

The AUR or the Arch User Repository contains build instructions for packages maintained by the community, and not binary packages. Each package in the AUR has a PKGBUILD file. This is a bash script that defines the package metadata, source URLs, dependencies, checksums, build and install steps. This file is uploaded to the AUR's git repository (at aur.archlinux.org/repo-name.git). Again, no binaries are hosted here.

To install a package from the AUR, the user clones this git repository and run the makepkg command (usually as makepkg -si to build and install). It will refer to the PKGBUILD file to download the source code or binary files, it will verify the checksums and PGP signatures, resolve dependencies via pacman and build the package locally, producing a .pkg.tar.zst file which can be installed using pacman. Keep in mind that at no point will pacman interact with the AUR. Note that AUR packages are not officially trusted as they are submitted by the users/community. Therefore, inspect the PKGBUILD file yourself before running makepkg to ensure it's secure.

Debian has a similiar slightly similar thing called PPAs (Personal Package Archives). You can learn more about it here.